Advertisement [ ? ]

Site Links

- Lease Calculator

- Advertise on 11,500+ pages

- My Car ongoing Review

- Members' Chat

- Cars For Sale

- Car Dealers

- Honda "Fit" Manual

- Hyperflex Bushings

- For Sale

- Fix your Car

- Car Manuals

- other manuals - Reference Materials

- DIY Repairs

- Articles

- Video

- Link with Us

- Search Help

- Code your Mac!

- Fly, race, anything R/C

- DIY repair guides

- Z-Seven

- Mechanic's Blog

- Free Files

Fuel System Diagnostics: Finding the Best Approach

With today's computerized engine controls and electronic fuel injection, it's hard to separate the fuel system from other systems when it comes to driveability and emissions diagnostics. Symptoms such as hard starting, stalling, hesitation, loss of power, poor fuel economy, rough idle, misfiring and elevated emissions can be caused by any number of things. So your job is to zero in on the most likely causes using the quickest and most effective procedures at your disposal. Sometimes this means ruling out other possibilities first, such as ignition or compression problems. Once these have been eliminated, you can focus on the fuel system and try to isolate the problem using the appropriate tests.

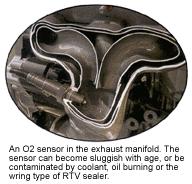

Before we go any further, let's define which parts we are talking about. The fuel system includes everything from the fuel filler cap, fuel tank, fuel pump, pump relay, fuel lines and filter to the fuel injectors, pressure regulator, fuel rail and throttle body. But our list may also include other parts and systems that influence or control the operation of the fuel system such as the PCM, oxygen sensor, coolant sensor, MAP sensor, throttle position sensor and airflow sensor (if one is used). There is also the idle speed control system, and the evaporative emissions system that captures and manages fuel vapors. We also have to include the fuel itself because "bad gas" that has been contaminated with water or higher-than-normal amounts of alcohol additives is still an often-overlooked cause of common driveability problems.

Code or No Code?

Fuel-related driveability and emission problems can be lumped into one of three basic categories:

- Code but no obvious driveability or emissions problem;

- Code and a driveability or emissions problem; or

- No code but a driveability or emissions problem.

The first two are usually easier to diagnose because you at least have a starting point (the fault code). The last one (no code) is the most challenging because you have only the symptom(s).

If the Check Engine light is on, you know the computer has detected something wrong and has logged one or more diagnostic trouble codes that correspond to the fault(s). When you hook up your scan tool, you know you are going to find some kind of information that should get you headed in the right diagnostic direction.

Without getting too philosophical, we all know that some codes are more helpful than others. It depends on the code, the conditions that are required to set it and the diagnostic procedures that follow it.

A code that indicates a particular sensor is reading out of range is usually a good indication that there is a problem in the sensor circuit. But if that code is accompanied by other codes, it often indicates an operating condition that is throwing the sensors off.

When there is more than one code, it sometimes makes matters worse because you may not be sure where to start. Should you go in numerical sequence, or should you step back and try to figure out what kind of condition would cause multiple codes to be set?

Choosing a Diagnostic Approach

Every technician develops his own approach to diagnostics based on past experience and the diagnostic equipment he has at his disposal. If you do not have a lot of fancy equipment, you learn to make do with what you have. If you do have the latest scan tool with all the adapters and cartridges, a 5-gas emissions analyzer, a multi-trace digital storage oscilloscope, a computerized engine analyzer, a flight recorder and a magic crystal ball that gives you insights into the unknown, you will typically use the tools with which you are the most familiar and that give you the best results in the least amount of time.

In other words, you can arrive at a diagnosis a variety of different ways using various methods, test procedures and equipment. But can you do it quickly and accurately? That is the real issue here. The more up-to-date your equipment is and the more familiar you are with how to use it, the better your results will be. You will waste less time chasing ghosts and spend more time actually fixing problems.

Fuel Injection Problem, What Is Wrong?

With that in mind, let's tackle a typical fuel-related problem. The vehicle is a late-model OBD II car with a four-cylinder engine. The Check Engine light is on and the engine idles a little rough and has some hesitation.

You hook up your scan tool and find a P0131 code that indicates the O2 sensor is reading low (lean) and a P0300 code for a random misfire. Is the O2 sensor bad or is it something else?

The problem might be a faulty O2 sensor, but more likely causes include a vacuum leak, low fuel pressure or dirty injectors that are leaning out the fuel mixture, causing the engine to run poorly and misfire. It might even be bad gas. What you do next will depend on the type of diagnostic equipment you have and what you think is the most likely cause.

You might begin your investigation by inspecting the intake manifold and vacuum hoses for obvious leaks. Finding none, you might hook up a vacuum gauge to see if intake vacuum readings are steady at idle and within normal range. A low reading could indicate a vacuum leak somewhere or possibly a leaking EGR valve. Further investigation would be needed to determine the cause if the readings are abnormal.

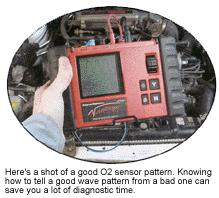

Next, you might use your scan tool, a DVOM or scope to look at O2 sensor performance. If the O2 sensor responds normally when you temporarily enrichen the fuel mixture by feeding some propane into the engine, or lean the mixture by disconnecting a vacuum line, you can probably assume the O2 sensor is OK. And if the engine control system is in closed loop (check loop status) and changes the injector dwell in response to changes in the O2 sensor reading, you can assume the feedback fuel control loop is doing its job, too.

Next, you might connect a pressure gauge to the fuel rail and check fuel pressure and the operation of the fuel pressure regulator. Does the pressure change when you disconnect the regulator vacuum line or pinch off the return hose? Low pressure readings would lead you to suspect a weak pump, while no change in the pressure readings when playing with the regulator would point toward a faulty regulator.

If fuel pressure is normal, you might look at the injector patterns on your scope. Does the dwell change when you goose the throttle or make the mixture go rich or lean?

You might also use your scope to look at the engine's secondary ignition pattern. When one or more (but not all) of the spark firing lines slope up to the right and firing time shortens, it indicates a lean fuel condition in the affected cylinders. A rich mixture is more conductive than a lean one, and requires less voltage to sustain a spark. On a fuel-injected engine, this could be a symptom of a dirty, clogged or inoperative fuel injector. The premature snuffing out of the spark can also be caused by poor cylinder breathing due to a rounded cam lobe or a leaky exhaust valve. A lean fuel mixture will also cause the firing KV to be higher than normal.

If the fuel mixture is running rich because the O2 sensor is dead or the feedback control system is stuck in open loop, the firing line portion of the secondary ignition pattern will show hairlike extensions hanging from the spark line. This is caused by the increased conductivity of the rich mixture. The KV firing voltages will also be lower than normal with a longer-than-normal spark duration.

Another alternative would be to hook up an exhaust emissions analyzer to look at carbon monoxide (CO) and hydrocarbons (HC). Higher-than-normal CO would tell you the mixture is running rich, while elevated HC would tell you there is a misfire or compression problem (lean misfire, ignition misfire or a burned exhaust valve). If you use the exhaust analyzer in conjunction with a power balance test, you can see if the HC readings change when each injector is shorted out. No change in HC would indicate a bad injector. If the change in HC is noticeably less on one cylinder than the others, it would tell you that injector is probably restricted and needs to be cleaned or replaced.

If you suspect dirty injectors, your next step might be to clean the injectors on the car. Or, if you have an off-car injector cleaner, you might pull the injectors, flow test them on the bench and clean them to see if normal performance can be restored (if not then you will have to replace the injectors).

According to some experts, a difference of more than 7 to 10% in flow rates between individual injectors on a multiport system is enough to cause noticeable driveability problems. Some cylinders will run too rich while others will run too lean. Ideally, all the injectors should flow within 3 to 5% of one another. If they don't, the computer will compensate for the leanest injector, forcing all the others to run rich.

When There Is No Fault Code

No-code driveability and emission problems are the ones everybody hates, especially when the symptoms are intermittent. In such situations, you have to go look at the symptom(s) and make some educated guesses as to what to look at first.

As before, how you approach a no-code problem will depend on what you have in your diagnostic arsenal. If you have an emissions analyzer, you might look at exhaust gases first. If you have a scope, you might examine sensor, injector, ignition or even the fuel pump waveforms. Since most technicians today own some type of scan tool, checking system data is as good a place as any to start, even when there is no code.

One of the first things you should check is loop status. The fuel system cannot deliver the proper fuel mixture if is stuck in open loop. If the engine fails to go into closed loop after it has warmed up or been driven, it may have a faulty coolant sensor or an open thermostat. The next logical step would be to look at the coolant sensor's output to see if it is reading normally or if its resistance changes as the engine warms up. No change in resistance or a reading that is out of range would tell you the coolant sensor is bad. To check the thermostat, you could use an infrared thermometer to measure coolant temperature at the thermostat outlet after the engine has warmed up. If low, the thermostat may be open, missing or the wrong temperature rating for the engine.

You can also look at short-term and long-term fuel trim to see if the engine is running rich or lean. If the system is going into closed loop, look at the TPS and MAP inputs to make sure they are changing when the throttle position changes.

Another Scenario

At the last International Automotive Technicians Network (iATN) convention in Dearborn, MI, a roomful of top technicians from all over the country was challenged to correctly diagnose several real-world driveability problems. They were given a description of some vehicles and their symptoms, then allowed to view actual test data that was taken from the vehicles using a variety of different diagnostic tests and equipment.

The challenge was to figure out which diagnostic tests and equipment would provide the most useful information, and to then analyze this information to come up with a diagnosis. It proved to be a difficult task because opinions differed as to what data should be looked at first, and what the data actually meant. Some people resorted to making wild guesses in an attempt to solve the problems.

One example that stumped a lot of technicians was a car that would start and run fine when cold, but had a hot-start problem. It would crank but not start. It had fuel, spark and compression. Fuel pressure and vacuum readings were normal. Coil resistance, spark plugs and wires were all within specifications.

The hot-start problem turned out to be a bad coolant sensor. The sensor was preventing the fuel system from going into closed loop, which created a rich mixture that flooded the engine when a hot start was attempted.

The diagnostic approach for solving a no-start condition that evolved from this was to:

- Check for spark to rule out ignition problems.

- Check for fuel to rule out an empty tank, dead fuel pump or plugged fuel line.

- Check compression to rule out a broken cam, timing chain or OHC timing belt.

If all of the above are OK, remove and examine a spark plug. If the plugs are wet, it would tell you the engine is flooded due to too much fuel. The underlying cause would be a defective coolant sensor or leaky injector(s).

Another approach when confronted with a no-start condition is to check cranking vacuum. It should usually be at least 3". If lower than this, there is a compression problem. Also, look at the amount of HC in the exhaust. If you see at least 7,500 ppm of HC, there should be enough fuel to start. If the HC reading is below 7,500 ppm, there is not enough fuel.

On many vehicles, a no-start can occur if the oil pressure switch is bad. The oil pressure switch is wired into the fuel pump relay circuit to cut voltage if oil pressure is lost. This is to prevent fuel from spraying out of a ruptured fuel line in the event of an accident. Some vehicles also have an inertia crash switch hidden somewhere in the bodywork (look in the trunk, under the back seat or inside the rear seat side panels) to cut off fuel in case of an accident. An inertia switch can be reset by pressing its reset button.

Hard starting on some older fuel injected systems can be caused by a faulty cold start injector. A timed relay energizes the injector when the engine is cranked to provide extra fuel. Most problems here can be traced to electrical faults in the control relay or wiring. Use a test light to check the cold-start injector when the engine is cranked. No voltage means the relay (or its fuse) is bad.

Leaky Fuel Injectors

Wear in the injector orifice and/or accumulated deposits can sometimes prevent the pintle valve inside an injector from seating, allowing fuel to dribble out the nozzle. The extra fuel causes a rich fuel condition, which can foul spark plugs, increase emissions and cause a rough idle. A carbon-fouled spark plug in one cylinder of a multi-port EFI engine usually indicates a leaky injector. If cleaning fails to eliminate the leak (which it can if dirt or varnish are responsible), replacement will be necessary.

Idle Problems

Idle problems can usually be traced to an air or vacuum leak, or in some cases, a faulty idle air bypass control motor or plugged idle bypass circuit. Leaks allow "unmetered" air into the engine and lean out the fuel mixture. The computer compensates by richening the mixture and closing off the idle bypass circuit. One of the symptoms of a vacuum leak, therefore, is a bypass motor run completely shut.

Plugged Fuel Filter

A plugged filter can restrict the flow of fuel and starve the engine, causing a loss of power at high speed, a lean fuel mixture or a stalling/no-start condition if the blockage is severe. The easiest way to check the filter is to remove it and attempt to blow air through it.

If the filter is plugged with rust or sediment, it is probably a good idea to drain and clean the fuel tank to prevent a repeat failure. If the tank is badly corroded inside, replacing the fuel tank would be recommended.

A restricted filter sock on the fuel pump pickup can cause similar symptoms, too. So, if the filter appears to be OK or replacing it fails to solve the problem, it may be necessary to drop the tank, remove the pump and inspect, clean or replace the filter sock.

Adapted from an article written by Larry Carley for Underhood Service magazine

Back to Driveability Diagnostics Emissions | Back to Info Main Page

Total messages: 0